When Nixon met Mao: ping-pong tables charted a path to the negotiating tables

- ‘Finding ways to bring the two peoples together, we just have to look for them’ is the reminder, more than 50 years later

- A chance exchange between an American player and a Chinese counterpart became the unlikely nudge for ‘the ping heard round the world’

It could have been a different sport. Another cultural event. A different time. The shaggy-haired American might not have taken a risk. And his gracious, well-groomed Chinese counterpart might not have responded.

A half-century on, as US-China relations hit new lows – and the two giants spar over everything from espionage and technology to Taiwan and the war in Ukraine – those who lived through the start of ping-pong diplomacy in April 1971 still marvel at how it all came together, what it led to and whether those days are lost forever.

“It’s the 64 million dollar question for all of us involved in this field. Our whole raison d’être is bringing people together and we have not been able to do that,” said Jan Berris, vice-president of the National Committee on US-China Relations. “Finding ways to bring the two peoples together, we just have to look for them.”

In retrospect, the pump was well primed, although few saw it at the time.

After two decades of intense US suspicion of “Red China” – Washington’s avowed enemy after Beijing’s 1950 entry into the Korean war – a containment policy and tight economic embargo, the United States was starting to see China as a useful lever for peace negotiations with Hanoi as the Vietnam war dragged on.

“We simply cannot afford to leave China outside the family of nations” with its then-800 million people, avowed anti-communist president Richard Nixon had written in 1967, the year before his election.

And many in Beijing, after decades of decrying American “aggression, control, interference and bullying”, were starting to consider economic reform and see Washington as a counterweight to the Soviet Union after several bloody 1969 border clashes.

But they needed a nudge, which would arrive in an unlikely form.

Ping-pong diplomacy: the game that changed US-China relations

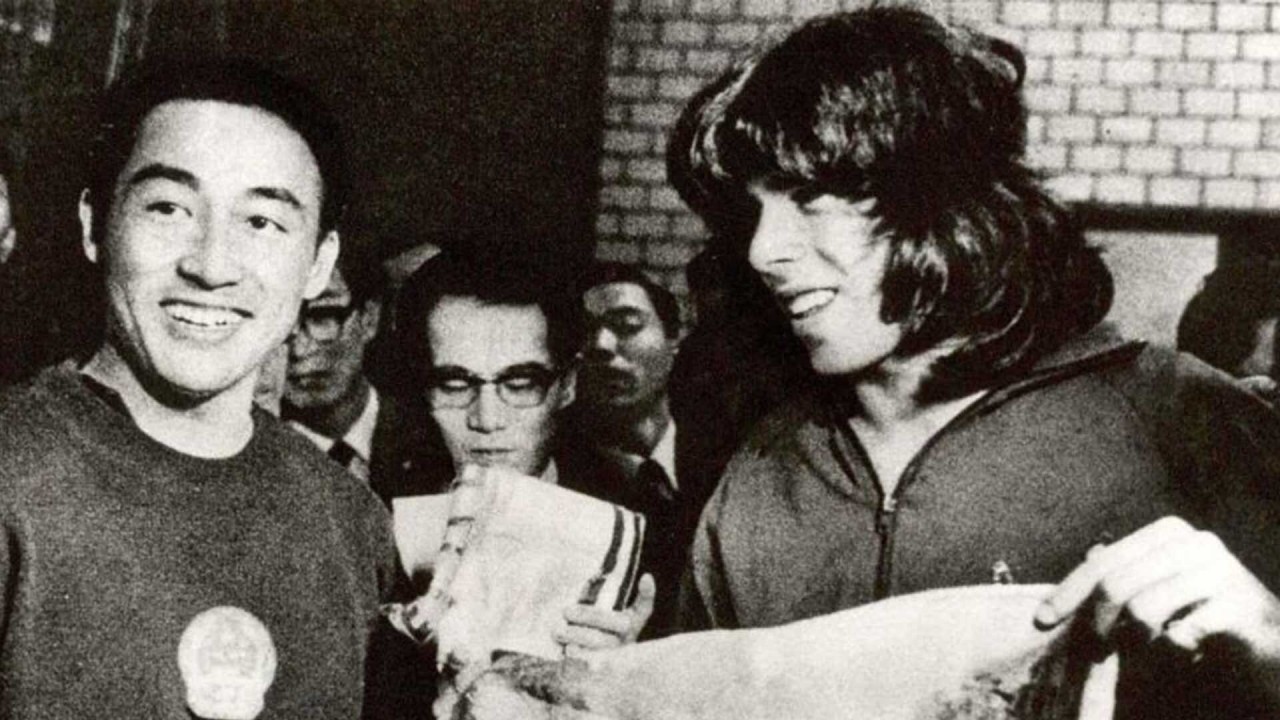

In a now famous incident, while competing in Nagoya, Japan, at the World Table Tennis Championship in April 1971, American ping-pong player Glenn Cowan, the oldest son of a middle-class family from New York, missed his bus after a practice session and jumped aboard the vehicle carrying the Chinese team.

The Chinese had been instructed to avoid Americans – chairman Mao Zedong reportedly warned them to be “ready for death” – so the sudden appearance by this self-described hippie was greeted with suspicion.

“I guess Glenn looked kind of baffled,” said American teammate Connie Sweeris, adding that the US team didn’t even realise until later he had missed their bus and was off making history.

The trip aboard the Chinese-laden vehicle took around 15 minutes “and I hesitated for 10 minutes”, Chinese team captain Zhuang Zedong recalled three decades later in a TV interview. “I grew up with the slogan ‘Down with American imperialism!’ This was the middle of the Cultural Revolution, and class struggle was rampant.”

“I was asking myself, ‘Is it OK to have anything to do with your No 1 enemy?’” Zhuang said.

Finally Zhuang mustered his courage, inspired, he said later, by a favourable comment about Americans Mao had made during a 1970 meeting with the US journalist Edgar Snow.

In a fateful moment, part of what Associated Press would call “one of the great diplomatic coups of their time”, Zhuang shook hands with Cowan and, rummaging through his bag, handed the American a silk-screen landscape of the Huangshan Mountains after rejecting various Mao badges, silk handkerchiefs and fans.

Cowan dived into his own bag to return the favour but found only a comb, and responded: “I wish I could give you something, but I can’t.”

China marks ping pong diplomacy 50 years on with call to cooperate

“Glenn felt really bad,” said Sweeris, adding that Cowan’s personality made all the difference in bridging that enormous divide. “He just goes for it,” she said. “He definitely would have gotten on any bus that came along.”

China in its Cold War isolation was an object of enormous fascination abroad, and photos of the unlikely meeting between the American and Chinese athletes emerging together from the bus quickly spread globally.

The next day, having crashed out of the tournament, Cowan visited an underground shopping mall in Nagoya and gave Zhuang a long-sleeved T-shirt with a peace symbol and the Beatles lyric “Let It Be”.

A reporter asked the American if he would like to visit China. “Of course,” he answered.

China had embraced table tennis in earnest after Mao declared it the national sport in the 1950s, although Western journalist Snow reported on members of the Communist military rather “bizarrely” playing the game in the 1930s after its invention by upper class Victorian Britons four decades earlier.

But the Cultural Revolution had taken its toll on Chinese table tennis, as with so much else, its world-beating players deprived of international competition or even much opportunity to practice for years.

Three of the team’s best coaches and players, including the country’s first international champion, had disappeared, either victims of suicide or beatings, with others sent out to the countryside amid accusations of “trophyism”, or chasing short-term glory abroad, according to Nicholas Griffin in Ping-Pong Diplomacy: The Secret History Behind the Game That Changed the World.

Premier Zhou Enlai, credited with helping revive the programme in the late 1960s, was instrumental in sending the team to Nagoya. And as it turned out, any rustiness did not show as the Chinese dominated, beating the Japanese to take gold, while the US team was eliminated early.

But much deeper geopolitical forces were at work behind the bouncing 2.7-gram (0.95-ounce) ball. Although Beijing and Washington had signalled a willingness to open dialogue through diplomats in New York and Geneva, both governments were hesitant.

“Mao knew the idea of befriending the Americans could get him torn down by the radical left. Nixon was worried about his own right wing,” Griffin wrote. “Without the support of their respective populations, Nixon and Mao’s imagined initiative was doomed.”

On hearing of the American team’s interest in visiting China that April, the Foreign Ministry initially rejected the idea. But on learning more about the chance exchange, Mao reversed course. Within two days, an invitation was extended to the rather shocked US team.

Death of Nixon’s ‘ping-pong diplomat’ Richard Solomon

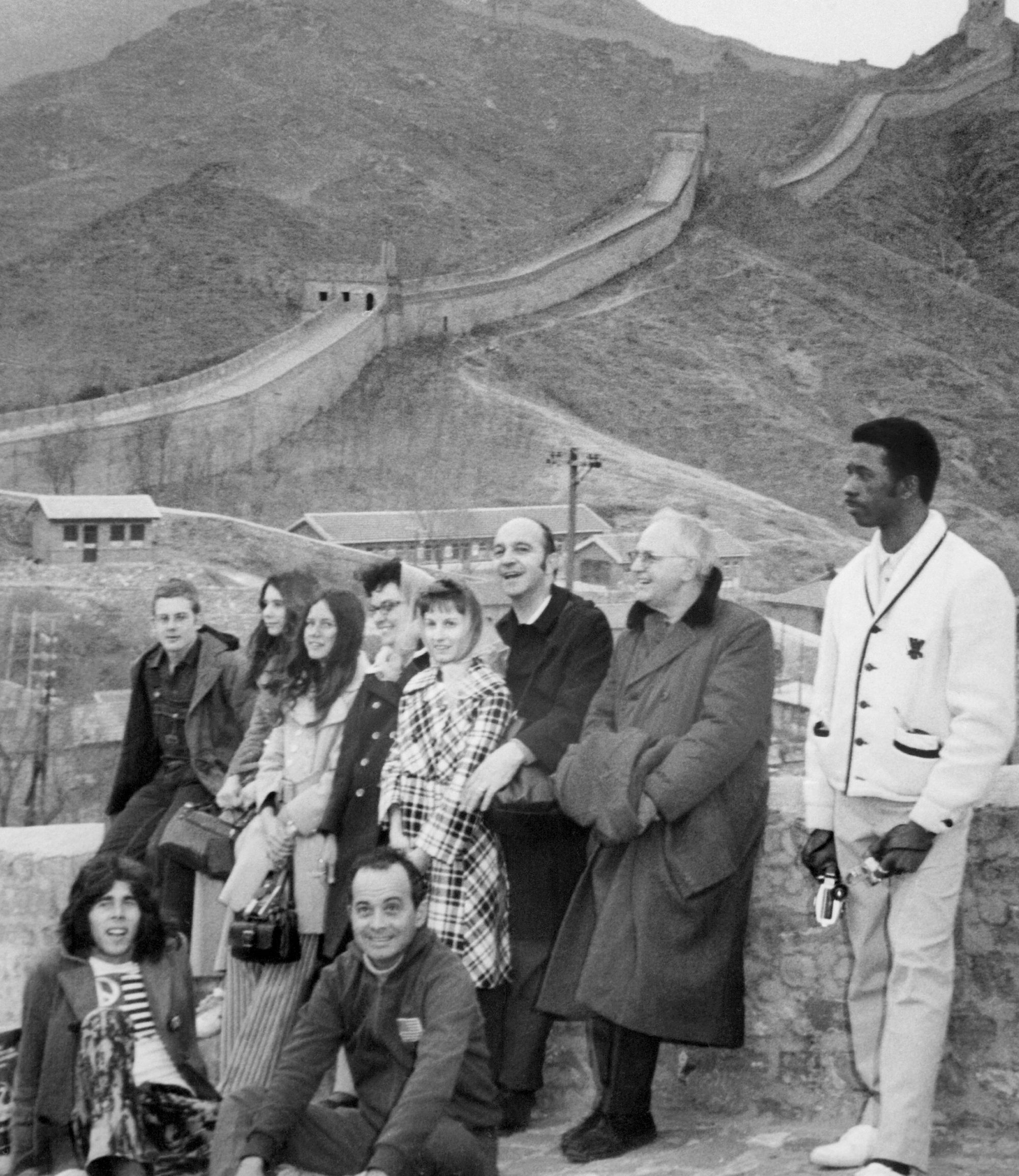

As the Americans hastily prepared to cross the “Bamboo Curtain”, they realized this was much more than a minor sports event, their every move tracked by reporters.

“It was just a nightmare,” said Sweeris, then a 23-year-old dental assistant. “I thought, boy, this is way bigger than anybody else thought.”

The prospect of entering isolated China was scary, Sweeris said, especially after armed guards on the border with Hong Kong took their passports: “I thought, oh boy, here I am in a communist country with no passport.”

As the two worlds collided, Cowan’s shaggy hair, floppy yellow hat and purple tie-dyed jeans drew stares throughout the trip, as did fellow teammates Judy Bochenski’s miniskirt and John Tannehill’s denim overalls.

And in an indication of the rapid ideological U-turn under way, team president Graham Steenhoven noticed at one stop that a “Welcome American Team” banner was hung over a wall painted with the slogan: “Down With the Yankee Oppressors and Their Running Dogs!”

The food was also an adjustment for the Americans, who dined on century eggs, sea cucumbers and other exotic dishes at countless eight-course banquets.

“I had some exposure to Chinese food, but American Chinese food,” said Sweeris. “I could eat the broth, but I wasn’t about to eat the chicken feet.”

At one point the premier asked Steenhoven if the team had any criticism of the trip and he told Zhou he did. “The whole audience kind of fell silent and gasped like, ‘Oh no, what’s he going to say?’” Sweeris said.

Steenhoven’s response: “You feed us too much,” Sweeris recalls. “And everybody laughed.”

On returning, the delegation became instant celebrities. A few days later, Nixon eased Chinese travel bans and trade embargoes, leading to his historic visit to Beijing 10 months later.

April 1972 saw a reciprocal eight-city US visit by the Chinese team, helping cement ping-pong diplomacy’s role in history.

“I heard President Nixon say, ‘Can you believe it that they’ve used ping-pong to open up the door?’” Sweeris said. “I think he wanted all the glory.”

Cowan died in 2004 at age 51 of a heart attack, and Zhuang succumbed to cancer in 2013 at age 72, reportedly after becoming embroiled in political turmoil following Mao’s death.

Those involved said there were good reasons this particular sport helped nudge the two nuclear adversaries together and launch what Time magazine called “the ping heard round the world”.

Nagoya, China’s first international event in years, provided the opening. Serendipity was also a factor, as was the fact that Zhuang, “who was a very warm, lovely person, had the guts to go up and talk to him,” said Berris, who organised the 1972 reciprocal tour to America led by the star Chinese player.

“This Zhuang Zedong not only plays table tennis well but is good at foreign affairs,” Mao reportedly said.

Finally, the sport played to China’s strength. “It probably could have been soccer,” said Berris.

“But first of all you have a sport in which the Chinese excel, and that gave them supreme confidence that they could hold their own in something. They certainly wouldn’t have done that for baseball or for American football, or for basketball.

“But with ping-pong, yes.”