Monday, October 27, 2025 | 12:00 PM EDT

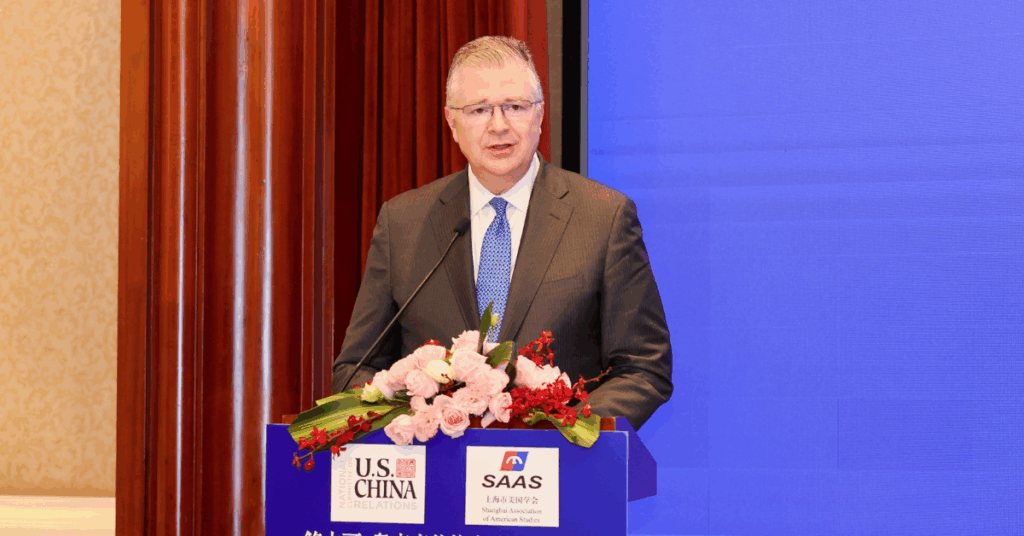

The fourteenth iteration of the Barnett-Oksenberg Lecture on Sino-American Relations was held in Shanghai on October 27, 2025. This year’s speaker was The Honorable Daniel Kritenbrink, Partner, The Asia Group; former ambassador to Vietnam and assistant secretary of state for East Asia and Pacific Affairs. The commentor was Professor Wu Xinbo, dean of the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University, director of Fudan’s Center for American studies, president of the Shanghai Association of American Studies, and vice chair of the Barnett-Oksenberg Lector Organizing Committee. Generous support for this year’s event came from Citi, Coca-Cola, Delta, DLA Piper, Qiming Venture Partners, and Wynn Resorts

Click here for more information on the Barnett-Oksenberg Lecture series, including videos, podcasts, and transcripts for previous lectures.

Listen to Ambassador Kritenbrink’s remarks below:

Watch the full lecture below:

EVENT TRANSCRIPT

OPENING REMARKS

Paul Liu:

Welcome to the 14th Barnett–Oksenberg lecture. It’s really good to see a lot of old familiar faces in the crowd, and I noticed there are a lot of young people also, which I suspect are from the Johns Hopkins Nanjing Center and from NYU. So, if you can raise your hands, all the young people and also the students from Shanghai University.

Allow me to make some brief remarks about the lecture series, this being the 14th iteration since the lecture series began in 2005. Just as background, the lecture is meant to honor Doak Barnett and Mike Oksenberg and their contributions to Sino–American relations. Doak and Mike were two American scholars and policymakers of distinction whose writings and actions had a powerful impact on bilateral relations dating back to the 1960s.

Doak Barnett was born here in Shanghai, not far from here. In fact, his childhood home is about a kilometer and a half away, just south of Tanggu Road. Doak had a great affection for this, the city of his birth. After graduating from Yale, he returned to China as a journalist. Doak went on to teach at Columbia University and Johns Hopkins University, where an entire generation of American China scholars were influenced by his voluminous teachings and writings. During the 1960s, Doak was one of the earliest voices calling for a dialogue with China despite the deep differences at that time between our two countries. His testimonies to Congress, his behind-the-scenes efforts, and his advice to people such as President Johnson helped to influence the process of changes in attitude toward China.

Michel Oksenberg, in turn, was an outstanding student of Doak Barnett while getting his PhD at Columbia. Mike went on to a long and distinguished teaching career at the University of Michigan, where he raised an entire generation of scholars to understand China better. Mike eventually served in President Carter’s National Security Council. At the ninth Barnett–Oksenberg lecture in 2014 here in Shanghai, President Carter underlined the critical role Mike played in the normalization of relations.

Both Doak and Mike were scholars of distinction who straddled both academia and policymaking. They both had a great admiration for China’s culture, history, and traditions, yet advocated hard-headed and realistic policy driven by national interests. They both took a long-term view on the incredible possibilities of relations between our two countries, despite the inevitable tensions arising from deeper and broader engagement. I knew both Doak and Mike, and I believe they couched their realism with a deep empathy and respect for the common humanity shared by both the American and Chinese peoples. This is something which is increasingly forgotten in today’s rhetorical atmosphere.

Like some of you here today, I had the privilege of studying under both Doak and Mike. And although Doak and Mike have passed, we continue to honor them. And by honoring them, we also honor the many people in both countries who strive to maintain the foundation of the relationship between the U.S. and China even in these very trying times.

The lecture format is purposely structured to be a dialogue which includes your involvement as an audience. An American speaker’s lecture, which is not pre-reviewed or edited, is commented on by a Chinese commentator, and the audience is free to ask questions in an open forum. When we established the lecture, our assumption was that the bilateral relationship would have its periods of volatility, but we also felt that engagement and frank dialogue would be an enduring requirement. This is especially true for today, especially now in the midst of competition and engagement. Finding areas of cooperation and engaging in mature, direct dialogue are even more important, and I’m sure the Ambassador will speak about this in his comments.

I want to recognize two people today in particular. First is the former head of the Shanghai Association of American Studies Ding Xinghao, now 92 years old. Ding Laoshi advocated for the lecture when it was just an idea. I also want to thank Ding’s successors at the SAAS, first Huang Renwei, who cannot be here today, and now Professor Wu Xinbo. Thank you very much.

Second, I want to recognize Jan Berris, vice president of the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations. I call Jan the unofficial U.S. Permanent Secretary of our bilateral relations. Jan has been on the Committee for over 50 years and has played a critical and entirely tireless role in our bilateral relations.

Thank you both.

We would like to thank our sponsors whose generosity made this event possible. The sponsors this year are Citibank, Coca-Cola, King Ventures, BLA Piper, Delta Airlines, and Wynn Resorts. And a special thanks also to Ken Jarrett for his help in all aspects of this year’s lecture. Thank you very much.

We also want to particularly thank the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai for their continued support. Thank you, Eric, for your support, and their very able event team led by Karen Chu, and for their incredible work in managing all aspects of the logistics for today’s event.

Finally, as I said at the beginning, included in our audience are at least 70 Chinese and American students. They come from the top universities in Shanghai and from the Johns Hopkins Nanjing Center, where American and Chinese students live and study together, discussing the difficult issues and possibilities of our complex relationship. We also have students here from NYU Shanghai and Duke Kunshan. These young people are part of the future of our relationship, as are all of you. So, thank you all for your continued engagement in the future of Sino–American relations. Thank you again for coming.

Jan Berris:

Good afternoon, everyone. I’m delighted to be here. As Paul said, I’m Jan Berris, vice president of the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations and an old friend of many of you in the room. It’s always nice to be here because— Shanghai, is actually my favorite city in China – but please keep my secret. Unfortunately, I usually only get here once a year — for this lecture, so it’s always wonderful to be here, and we appreciate all of you coming.

Paul has thanked a lot of people, but one of the most important people he left out—because he’s very modest—is himself. So I’m going to thank Paul and tell all of you that we would not be here today if it were not for him. He’s a Chinese American, and his heart is in both countries, but in many ways, I think he’s a little more Chinese than he is American because he is a very, very filial person. After his two teachers died— Doak Barnett and Mike Oksenberg—he wanted to find a way to honor them. And to me, that is a very, very Chinese thing to do.

So, he called me one day. I’ll never forget; I was skiing in Vermont, and I came back from skiing, and there was this note that said that Paul was trying to reach me. I called him, and he told me this idea that he had, and he said, “Next time you’re in Shanghai, I want you to get together with me and Professor Ding Xinghao.” Professor Ding, who as Paul just mentioned advocated early on for this event, Paul, and I sat together one night and spent several hours thinking about what would be the best possible way to honor Doak and Mike and came up with the idea for this lecture.

I’m just really pleased—and I know that Mike and Doak would be extremely pleased—to know that this lecture has now gone on for so many years, and that we can fill a room with people who still want to come to hear, and to talk about, and to think about U.S.–China relations, and the nature of the relationship, and how we can make it better. And that’s a very important thing to do in these very difficult times.

Paul mentioned several people who are here but there are two people I want to add to that list, and these two people also come every single year even though they no longer live here. It was sort of easy when they lived in Shanghai or were up in Beijing. That is Doak’s nephew, James Barnett, and his wife, Mei. James, I know you walked in, but I don’t know where you’re sitting.

One other addition I would like to make, and I’m not going to embarrass him by having him stand up, but Paul mentioned that there are students here from several universities and he mentioned all of them. Well, there is one more university that’s represented here, and that’s Shanghai Technical University. I’ve been in China for the past week. I first went to Guizhou and spent four days there talking with a lot of people about strategic security issues for a dialogue that the National Committee runs on that subject. Then I went to Beijing to meet more people. Yesterday I took a train down from Beijing to Shanghai, and I sat next to a really lovely young man who is a graduate student at the Shanghai Technical University. He was extraordinarily helpful to me in all sorts of ways, and so I asked him if he might want to come to this today, and he’s here too.

So I just wanted you to know that you have a wide range of schools that are represented, and I think it is really important that we have such a strong showing from the younger generation because they are the ones who are going to have to figure out a better way to make the relationship work than we older people who tried our best. The relationship, as everyone in this room knows, is a very mercurial one. It’s had its ups, and it’s had its downs. We are right now in a sort of stable down position, but hopefully there will be a meeting between our two presidents sometime this week and hopefully that will start us on the progression of making the relationship better.

Our goal at the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations is to help people make that happen, to make the relationship better, to provide more opportunities for Americans to come to China to better understand it, and for Chinese to come to America. Because neither of us should be listening to the politicians nor the media. We should come to the another country, spend time there, and make our own decisions on what is important and how we can work together for a better future.

So, I’m going to stop talking and turn it over to…

Dr. SHAO Yuqun:

Thank you, dear Mr. Paul Liu, Ms. Jan Berris, Ambassador Dan Kritenbrink, Professor Wu Xinbo, and Professor Ding. Ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. I’m Shao Yuqun. I lead the Institute for Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau Studies at the Shanghai Institute for International Studies. Today, there are four graduate students from SIIS also joining this audience. I’m also the vice president of the Shanghai Association of American Studies.

On behalf of this Association, I’m very delighted to welcome Ambassador Kritenbrink to Shanghai as the speaker for this year’s Barnett–Oksenberg Lecture on Sino-American Relations. I’ve already met with the Ambassador twice this year, once in Washington, D.C. and once in Shanghai recently, and have had great closed-door discussions on our bilateral relations. I’m very glad that he’s back in Shanghai again and would like to share his insights with a much bigger audience.

The Shanghai Association of American Studies is a non-governmental organization founded in the year 2000, with 120 individual members who conduct research on the U.S. economy, politics, security strategies, social issues, and of course the development of China–U.S. relations. One of the association’s missions is to increase public understanding and knowledge of the United States and co-hosting this lecture with the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations is a key part of this effort. This year marks the 14th anniversary of this lecture, and its importance in enhancing mutual understanding between the two societies has never been more important than now.

China and the United States are both proudly nationalistic nations, often making it difficult for the other to understand, let alone comprehend. What they really care about is how to make their own country better, not to make enemies with each other. However, due to the pandemic and various other reasons, exchanges between the two sides, especially exchanges between think tanks and universities, are becoming increasingly difficult. This requires us to carry forward the spirit of Doak Barnett and Mike Oksenberg, who overcame difficulties and actively promoted the normalization of China–U.S. relations, and make our due contribution to helping today’s China–U.S. relations get out of the predicament and enter a truly stable stage.

We are currently at an interesting historical moment. Yesterday, the Chinese and American teams just concluded an important meeting in Malaysia. We are expecting a summit meeting between our two presidents while they are in Gwangju, South Korea, attending the APEC summit. This afternoon, I was interviewed by a German journalist who asked me if this possible summit would be symbolic or groundbreaking. I said neither. The meeting is definitely not symbolic, because the summits between the two presidents have played a leading role in bilateral relations, as we have seen. However, due to the many structural problems in the bilateral relationship and the difficulty of fundamental adjustments in the American perception and strategy towards China in the short term, the meeting is unlikely to be groundbreaking, and it’s very likely that the bilateral relationship will further deteriorate after the summit.

In the process of negotiating while confronting each other, China and the United States are exploring both the ceiling and the floor of this bilateral relationship and gaining a new understanding of each other. Perhaps this is the new normal of the bilateral relationship. I like Ambassador Kritenbrink’s speech title, “Reflections on a Relationship that Shapes the World.” In the 1990s, China–U.S. relations were often characterized by the three T’s: trade, Taiwan, and Tibet. As we moved into the 21st century, the relationship was seen as a bilateral one with significant regional impact. Now, however, it is undeniable that this relationship will determine the future trajectory of human society.

Thus, we must engage with research and promote China–U.S. relations with a sense of mission to serve the well-being of all humanity. With that, I’ll hand it over to Ambassador Kritenbrink for his remarks. Dan, you have 30 minutes.

Lecture

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

Good afternoon, everyone. Distinguished guests, colleagues, and friends, I really just can’t tell you what a tremendous honor it is to be here today for this year’s Barnett–Oksenberg lecture, and to do so here in Shanghai, a city that has long stood at the crossroads of China’s engagement with the world. I want to say in particular; I’m deeply moved at this moment to see there are so many people here who still care about the U.S.–China relationship at least as much as I do, and I’m particularly moved to see so many young students here today. I wish I could change places with you, and I’m looking forward to having a conversation here with you this evening.

Let me begin by expressing my deep gratitude to the Barnett–Oksenberg lecture organizing committee, especially the chair, Paul Liu. Paul, I don’t think we’ve appropriately recognized you, so Paul, thank you. And the vice chairs, the inimitable Jan Berris and Professor Wu Xinbo. I also want to thank my friend Dr. Shao Yuqun. Pretty much what she said—I thought that was a brilliant summation. You’re going to listen to me for the next 20 minutes, but it’s pretty much what she said. Dr. Shao, I thank you for your friendship, I thank you for your scholarship.

I also want to thank our hosts, the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations and the Shanghai Association of American Studies. My thanks as well to our cooperating partners, the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai and the Shanghai Institute of American Studies.

This lecture series, of course, honors A. Doak Barnett and Michel Oksenberg, two scholar-practitioners who helped generations of Americans and Chinese—academics, policymakers, and the public—better understand one another. Reflecting on Professor Barnett’s passing, Professor Oksenberg at the time wrote that his mentor “brought reason to the often-uncivil American debate on China policy.” Throughout his life, Doak fought the good fight for a rational and realistic policy toward China. Years later, Oksenberg’s own students recalled that Mike used his seemingly bottomless reservoir of energy to make China and America understandable to each other, and on that basis, he strove to develop realistic ties that would serve both countries. I believe those words still resonate and inspire us today.

Their influence has endured through the many they mentored—scholars and officials such as Ken Lieberthal, Cui Tiankai, Elizabeth Economy, David Shambaugh—each of whom has contributed mightily to this relationship, and each of whom has taught me a great deal. I’m also particularly honored to speak tonight because my own heroes have always been educators and scholars. I grew up wanting to be a professor and somehow got distracted by a career in diplomacy, but maybe I’ll make it back home someday. But, like many here, I owe immense debts to my own professors, first at the University of Nebraska–Kearney, later at the University of Virginia, where I learned about China from Brantly Womack and Tony Leng. I learned about diplomacy and international relations from Ken Thompson, David Newsom, and Len Schoppa. Their example, and that of Professors Barnett and Oksenberg, taught me the enduring value of scholarship informed by experience and experience guided by scholarship. I will do my utmost to honor their legacy here this evening.

Now, when Jan Berris invited me to deliver this lecture, I initially hesitated. I was humbled by the stature of those who have spoken before me, and I was daunted by the seriousness of this topic. But I agreed because of my deep respect for the National Committee and because U.S.–China relations—the world’s most complex yet consequential relationship—have shaped not only global affairs but also my own 31-year diplomatic career.

During our limited time this afternoon, I won’t attempt to resolve the great questions that have perplexed our two countries for more than half a century. Instead, I will try to do three things simply and, I hope, succinctly. Jan told me, Dr. Shao, I only have 15 to 20 minutes, so that’s my goal. But, in our 15 to 20 minutes together, I will try to do three things. First, I will share five lessons from my decades as a U.S. diplomat working on China. Second, I will offer five observations on the relationship today on the eve of a summit between our two leaders in Korea. And third, I will discuss five thoughts and hopes for the path ahead. You can tell, in great Chinese style, I’ve come up with the “three fives” for the U.S.–China relationship. So, after I deliver my three fives, I then look forward to Dr. Wu Xinbo’s commentary and corrections, and to many questions from this audience.

First, allow me to share my reflections on a diplomatic career shaped largely by U.S.–China relations. Over three decades in the U.S. Foreign Service from January 1994 until January of this year, two-thirds of my career focused directly on China—from two years of language training, very humbling language training, in the mid-2000s, to eight years at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing with my family, to assignments as the China desk director at the NSC, Senior Director for Asia, U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam, and Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. China was the constant thread.

During my career, I witnessed our relationship evolving dramatically, becoming significantly more complex and suffering a significant downturn. I take no satisfaction in that assessment. But we have moved from an era largely defined by shared interest and cooperation within which we managed competition and differences, to one now defined primarily by strategic competition within which we struggle to find limited cooperation.

During that same period, we’ve observed China’s stunning rise. Yet we’ve also observed the emergence of a China that is often more assertive and coercive abroad and more restrictive and suspicious at home. With that background, let me share with you the five lessons that I learned.

First, the enduring importance of people-to-people ties. My earliest years at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing were doing what American political officers back then were paid to do: talking, eating, and yes, often drinking with smart, engaging Chinese counterparts. They were scholars, journalists, students, activists, and officials, many of whom displayed courage, civility, and pride in their nation’s resurgence. Those relationships—hundreds of relationships—and the insights they offered became a key foundation of my own understanding of China. I was struck by the reservoir of goodwill that many Chinese held toward the United States and by the many aspirations that we shared together, even as the legacies of China’s century of humiliation and the bitterness they generated were still never far below the surface. Those experiences also reminded me always to distinguish between the great Chinese people, whose warmth and ambitions are unmistakable, and the policies of the party-state. Sadly, such exchanges are harder today. The atmosphere of suspicion has chilled the informal connections that once animated our work. Yet they remain irreplaceable, and we should do everything possible to preserve them. I still have the utmost respect for the Chinese people.

Second, diplomacy matters—especially at the leader level. It will come as no shock to you that I’m a retired diplomat; I believe in talking to people. But I did learn throughout my career, I’ve seen both the promise and the limits of diplomatic dialogue. Too often, dialogue risks becoming ritual. I recall years ago when our two countries maintained more than 60 formal dialogue mechanisms, we still had few real exchanges. Dialogue must be candid and outcome oriented. Yet, while we must avoid performative interactions, it’s also clear to me that the most dangerous moments in our relationship have been those of greatest tension, when communication broke down—including sometimes because our Chinese friends went dark during a crisis to focus on their own internal coordination.

However, when our leaders and our diplomats engage candidly, privately, regularly, and strategically, we better understand one another. We reduce the risk of miscalculations. We diffuse crises, and we occasionally agree to cooperate. I’ve seen up close the stabilizing power of leader-level diplomacy with China—from Bush–Hu, to Obama–Xi, to Biden–Xi. And, as I will discuss below, I believe the same dynamic clearly holds true today under the Trump presidency, perhaps more than ever before. Trust between our countries is scarce, but even limited trust between leaders and envoys can prevent the worst outcomes, place guardrails on competition, and provide leverage to conclude agreements. Leader-level diplomacy is especially important for our two systems: for China’s top-down governance, as well as for a U.S. system increasingly divided on the question of how to deal with China.

My third lesson: alliances and partnerships remain America’s greatest strategic asset and should remain a central element of a successful U.S.-China strategy. As I rose to senior roles during my career, I realized more clearly than ever that America’s alliances and partnerships are central to our security, our prosperity, and our success in dealing with China. Simply put, a sound China strategy begins with strong alliances. As the late, great Ambassador Richard Armitage used to say, “To get China right, the United States must get the region right.” Our friends in the Indo-Pacific look to Washington not for confrontation, but for steadiness—an America that upholds a rules-based order while competing responsibly. Most partners do not wish to choose sides; they wish to preserve the choice itself. That principle—strategic autonomy free from coercion—is one that all parties should respect. Sadly, many Chinese friends have misread, I think, America’s alliance network as encirclement or containment. But I strongly believe it is not. Our alliances are the inheritance of the post-war order, and it is an order in which China itself has obviously prospered.

Fourth, America’s strength abroad depends on renewal at home. During the final decade of my career, I increasingly observed that America’s ability to compete effectively with China rests not on our delivery of speeches or demarches in our respective capitals, but on the resilience of our economy, the deterrence of our military, the vitality of our democracy, and the unity of our people. We should focus less on persuading China to change and more on proving that our own system works—that our economy remains innovative, our governance effective, and our commitments to the region enduring. For Chinese friends convinced of U.S. decline, I would simply say there have been many moments in previous decades when America’s staying power in Asia had been doubted, and in each case those predictions have been wrong.

My fifth and final lesson is that competition between our two countries will only intensify, especially in technology. But our primary task is to manage this competition responsibly. If there’s one thing I learned over the course of my career, it is again that rivalry and competition between our two countries will continue to grow. But we must do all we can to minimize the risk of miscalculations that can lead to conflict. Particularly since Beijing’s announcement of “Made in China 2025,” the race to shape the industries of the 21st century has become the central arena of our competition. Both nations seek prosperity and security; neither will easily yield leadership.

Of course, this is not the only realm for our competition. We’re faced with a host of long-standing disagreements and issues such as peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait and in the East and South China Seas; the differences over human rights; these issues have been there for a long time. None of that will change anytime soon. But what I have learned—again, I will reiterate—is that our primary task should be to ensure that this competition remains responsible and peaceful.

Let me now turn to the extraordinary moment in which we find ourselves today and the anticipation surrounding the expected meeting between our two leaders on the margins of APEC in Gwangju, South Korea. Here, too, I would offer five observations.

First, this has been an unprecedentedly tumultuous year in U.S.–China relations, one that has taken us from a tariff war to a supply-chain war, to now a tentative search for stability. The Trump administration’s efforts to use primarily tariffs to re-industrialize the United States, restore critical supply chains, and reduce the trade deficit have been met by assertive Chinese countermeasures. After the two sides essentially fought this tariff and supply-chain war to a standstill, diplomacy has resumed, and an uneasy truce has emerged, anchored by discussions between Treasury Secretary Bessent and Vice Premier He Lifeng, and by phone calls between President Trump and President Xi.

Now, on the eve of our two presidents’ meeting in Korea, both sides profess a desire to stabilize the relationship. Yet, I think recent events underscore just how fragile this search for stability remains. The United States’s new 50 percent rule on technology exports and China’s sweeping global rare earths licensing regime illustrate how easily tactical actions can reignite strategic mistrust. In recent conversations with officials in both capitals, one hears the same refrain: each side felt aggrieved; each side believed it has been wronged and betrayed. Yet despite that bitterness, it’s been striking to me how quickly both sides de-escalated the situation over the past two weeks. And based on the news overnight, the framework that has reportedly been agreed to yesterday by Secretary Bessent and Vice Premier He in Kuala Lumpur is quite positive. Based on that, it appears that the meeting between our two presidents will, in fact, go forward, and will go forward in a relatively positive atmosphere.

I think what we’ll need to watch, however, is whether this framework is going to be implemented now or whether it will serve primarily as the basis for negotiations over the next 12 months, when it’s reported that President Trump will visit China early next year, and hopefully President Xi will visit the United States in late 2026.

Third, in this tense environment, I believe that leader-level diplomacy remains essential—perhaps more than ever before. As I’ve noted, historically, personal engagement between our presidents has played a key role in managing the bilateral relationship. I think it’s been that way since 1972. Stabilization appears likely to be the top priority coming out of the Korea meeting, just as the June 5 and September 19 Trump–Xi phone calls lowered tensions and outlined a diplomatic calendar for the months ahead. But it is clear to me that both sides also want concrete outcomes. For the United States, the President has focused on commercial purchases, especially of agricultural products, fentanyl, supply chains, and TikTok. For Chinese friends, they are reportedly looking at relaxation of U.S. tech and investment restrictions, tariff relief, and a reaffirmation of the U.S. One China policy and perhaps more. Beyond whatever deliverables may be announced now versus those saved for later visits, I believe the key is to use these channels to prevent the relationship from devolving into a test of wills.

Fourth, despite this flurry of diplomacy, the structural drivers of competition and suspicion will not change anytime soon. Both sides approach the other with considerable confidence. Each side believes the other needs it more; each side thinks it holds escalation of dominance. I have to say, though, based on my travels to China just over the last month, it is quite striking to me how confident Beijing has become, and the strength of China’s growing belief that it has the ability to manage Washington, shaped by lessons from the first Trump administration—namely that Beijing has learned that swift tit-for-tat responses command respect, and many Chinese friends continue to believe that China can “eat bitterness” longer than Americans can.

And finally, expectations of what this diplomacy can achieve must remain realistic. Any agreement this year, even at the presidential level, will likely deliver tactical stabilization, not a strategic transformation. The deeper forces shaping this relationship—divergent systems, mutual suspicion, global ambition—will continue to fuel competition. Yet even incremental progress toward predictability is valuable when mistrust runs so high, and tactical stabilization is obviously preferable to an out-of-control trade war.

Having reflected on past lessons and the current moment, let me close by offering five thoughts and hopes for the U.S.–China relationship going forward.

First, we must accept and responsibly manage a primarily competitive relationship between our two countries. As I’ve noted, competition between the United States and China is structural, not temporary. We should not apologize for this; in fact, I think we should embrace this fact. But at the same time, we must manage and channel this competition productively, ensuring that rivalry does not slide into hostility, miscalculation, or conflict. I was deeply struck last year in a meeting while I was still a U.S. diplomat. It was a meeting in Beijing with a very senior Chinese official in which he said, “Perhaps that is the best that we can do.” I believe it likely is, and it certainly is the most important thing that we can do. But if maintaining open channels and avoiding miscalculation and conflict is the best that we can do, then we must do it exceptionally well. That is our responsibility.

Second, I believe and hope that China should show that it can wield power responsibly. When I was Assistant Secretary, a foreign minister of a major regional country declared that the challenge posed by China is that China has weaponized much of its external engagements to advance its national interests in increasingly aggressive ways. I therefore believe that China’s challenge is to demonstrate that its rise contributes to regional stability, not unease. Chinese friends should not be surprised when countries around the region and the world, including the United States, react with concern—such as when Beijing unveils a global rare earths licensing regime.

Third, the United States must build its sources of strength both at home and with its allies and partners. As I’ve argued above, America’s credibility abroad begins with coherence at home. When we invest in innovation, education, and infrastructure, we compete from a position of confidence. And when we coordinate with allies and partners, we amplify that strength through collective action. I think those are the keys to effectively competing with China.

Fourth, I reiterate that diplomacy will remain indispensable despite its limits. Our channels of communication, including at the presidential level, have repeatedly proven their value in clarifying intentions, diffusing crises, and creating space for cooperation. Diplomacy will not eliminate competition, but it can prevent it from becoming a catastrophe.

And fifth, we must preserve people-to-people and business ties. Our nations remain deeply interdependent. Bilateral trade is still roughly 700 billion annually. Even as our competition—including in economic and tech sectors—intensifies, and we take steps to defend our interests and our companies, we must never allow strategic rivalry to harden into enmity between our peoples, or give in to the temptation to include restrictions on people-to-people ties as a source of asymmetrical leverage in a no-holds-barred competition. I still believe that the foundation of any relationship, including this one, is built on the links between our people. We must protect that. That is why I think the work of organizations such as the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations, the Shanghai Institute of American Studies, and others is more vital than ever before.

So, in conclusion, the relationship between the United States and China will remain the world’s most consequential and complex, marked by rivalry but also by the inescapable reality that neither of us is going anywhere. Neither of us will force the other into submission, and we should not try. Even as we embrace our intensifying competition, we are not doomed to fatalistic acceptance of a Thucydides trap. The future of U.S.–China relations will be shaped not by fate, but by choices—namely our choices. The spirit of Barnett and Oksenberg urges us to choose reason over rhetoric, realism over dogma, as we pursue, again, and I quote, “a rational and realistic policy towards China” and develop realistic ties that would serve both countries. That wisdom, I believe, resonates now more than ever.

Thank you very much for the opportunity to speak with you today. Dr. Wu, I look forward to your comments and to the audience’s questions. Again, thank you very much.

Commentary

Professor Wu Xinbo:

Thank you, Dan, for your excellent speech. You mentioned your education background. I understand you have got a Ph.D., but if you continue to work on your speech, then that will qualify you for a Ph.D., maybe at Fudan university sometime in the future.

Kritenbrink: I will take you up on that. Wu: Okay, I would love to.

Good afternoon everyone. Welcome to the annual event, the Doak Barnett- Mike Oksenberg lectureship. This lecture has been held over the last, how many years, maybe 14 or 15 years in Shanghai, and it has become an important symbol of the city’s commitment to understanding between China and the United States, as well as the commitment to enhancing bilateral relations.

I think Dan covered a lot of areas based on his experience of working in the U.S. government in the last 31 years. I remember I got to know him when he was working for the Obama administration at the China desk and then followed by the Trump administration as well as the Biden administration. So, he basically saw both the good old days as well as the bad days, as we are confronting today.

Let me start. I didn’t have the chance to read his speech in advance, but let me try to comment on the three key words he mentioned in his speech. First is “competition.” He keeps emphasizing that competition is a structural feature of bilateral relations today. Not a very long time ago, when we talked about China–U.S. relations — on both sides we would say this is a mixture of both cooperation and competition. But then suddenly, starting from Donald Trump’s first administration, when they talk about China relations, they only mentioned competition, and “cooperation” or “coordination” disappeared. The rhetoric has been resonated again and again by the Biden administration and now by Trump’s second administration.

So, I keep explaining to my students in class why suddenly the U.S. changed its definition of relations with China. Largely because they were shocked, surprised, and unwilling to accept the rise of China. So, they decided they should switch from engagement to competition as the effective way to forestall the rise of China.

Let me be very frank. Today, when we keep talking about competition, I think the U.S. didn’t benefit that much in the last seven or eight years by emphasizing only competition in relation with China, because competition doesn’t really promote U.S. competitiveness—even though it believes the other way around. And also, when we talk about competition, let’s always remember that in dealing with China, cooperation is still there—like it or not—in bilateral context, in multilateral context. So, what’s important today is not that we should manage the competition, but more importantly, we should pay due attention to the necessity of promoting cooperation in bilateral relations. We need a more balanced, more rational approach to this relationship. Emphasizing too much competition will only get bilateral relations derailed from the right track. So that’s the first key word I want to comment on: competition.

The second is about “alliance.” Dan mentioned in his speech that alliance is very important to U.S. China strategy, and alliance is not intended to deal with China. Well, if we look at the policy behaviors on the part of the U.S. when it comes to its alliances in this region, I think alliance has been used as a very important leverage in U.S. strategy towards China. Let’s be frank and honest that the U.S. has found alliance as a very important strategic asset in dealing with China, especially on the security front, but more and more on the economic front when it comes to technology control or the sanctioning of Chinese entities.

So, alliance is important to the U.S., but I think gradually the U.S. should realize the limit of this leverage in dealing with China. Because today—I just came back from a trip to Southeast Asia—I can tell you that U.S. allies and partners in this region are now very suspicious of the U.S. under the Donald Trump administration. Not only because they suffered from U.S. tariffs, but they are more and more skeptical of U.S. commitment to its security presence in this region and to its security protection of allies. So even though people still say alliance is very important to U.S. China strategy, I think its utility is declining rather than increasing, not because of China but because of U.S. policy towards its allies and partners.

The third key word I want to comment on is “diplomacy.” As a career diplomat, I can understand why Dan keeps emphasizing the importance of diplomacy in relations with China, and I agree. In the last several decades, skillful and successful diplomacy played a very important role in managing this relationship in times of change and turbulence. But today, if we look at Donald Trump’s China policy—if he has a policy—I think he is very much issue-specific. If he cares about trade, he thinks about tariffs; if he cares about some kind of issue, he thinks about tariffs; if he thinks about rare earth issues, he thinks about tariffs. Basically, this is an issue-specific, issue-oriented diplomacy.

Let’s remember in the late Biden administration we had around 20 dialogue mechanisms between the two countries, right? In the good old days, we had 60 or even more. But even in the Biden era, we had almost 20. Today we have only one: trade. And it’s not really talks. There is no diplomatic dialogue, no security dialogue, no dialogue between law-enforcement agencies between two sides, no dialogue mechanism with regard to people-to-people exchanges, which Dan has just emphasized. So, the problem is that this administration doesn’t believe in the value of diplomacy. Even though the Chinese side has pushed again and again for strategic communication, it’s not happening. It’s not happening. Now, when the two leaders are going to meet, we haven’t seen any significant diplomatic coordination between the two sides, as far as we know. So that is very rare compared with the history of this relationship in the last several decades.

Dan, as a career diplomat, certainly has contributed a lot to this relationship through his hard work over the last decades. I don’t think he would believe now is the right time to talk about the importance of diplomacy in bilateral relations, because the reality is that people in Washington, in the White House, are not paying much attention to this topic.

Now, Dan just offered five points as a reflection on current China–U.S. relations. Let me try to match that with my five-point reflection as a way to complement, not to supplement, his remarks, based on my reading of U.S.-China policy since the first Trump administration.

The first point is that trying to slow down or even to stop China’s development through competition, containment, suppression—whatever it is—will not work. At most, you may slow down China’s development in the short term, but not in the long term. Dan just mentioned his impression during his recent trip to China: that the Chinese side has become more confident. Because after suffering in the short term in the last several years, now we realize maybe the so-called competition from the U.S. side is a good thing for China in the long run, because we have to emphasize more on indigenous innovation, we have to emphasize more on domestic consumption, and we have to pay more attention to developing trade and economic ties with Global South countries, etc.

So I think when competition first came out, people clearly said this is a window of opportunity for the U.S. to win competition with China. Now, seven or eight years after this, I think it is very clear that the U.S. cannot expect to stop China’s development through competition.

Second point is that containing or suppressing China will not help promote U.S. competitiveness. After all, the U.S. has to invest domestically to improve itself. And to some extent, I think because of the destructive competition with China, it hurts U.S. competitiveness in many ways. Let me give one example: if I’m in charge of U.S. policy, one thing I want to do with China is to get China’s assistance in improving U.S. infrastructure, which is so poor, so outdated. It’s making the U.S. look like a sort of “third world” country. Without modern infrastructure. How can you develop everything, including manufacturing capacity? But the U.S. is too much influenced by the concept of competition. So, it doesn’t want to trade with China, it doesn’t want to get Chinese investment in the U.S., it doesn’t want to cooperate with China in green technology and other areas in which China is already leading ahead of the U.S. So, I think, in this way, this kind of destructive competition doesn’t hurt China but hurts the U.S.

The third point is that, after this year’s trade war, I think it’s very clear to Washington that the U.S. has to rely on China. Decoupling from China is unrealistic. Trump always believed that the entire world would rely on the U.S. market. On the other hand, in a globalized world economy, the U.S. also relies on other countries, especially China, for the supply chain. The U.S. cannot walk away from the commodities that China sells to the U.S.—not to mention rare earth and crucial minerals. So, if the U.S. tries to decouple from China, it only ends up hurting its own economy. I think that is very obvious from the recent trade war between the two countries.

Next, number four: the U.S. does not just need to cooperate with China on the economic front. It also needs China’s cooperation in diplomatic and security areas bilaterally, regionally, and globally. Dan, as a career diplomat, I trust he understands the value of cooperation with China on many regional and international issues—even though he intentionally did not emphasize this in his speech. But I think from the bottom of his heart he should understand the importance of this issue. And I understand on Thursday when the two leaders meet in South Korea, President Trump will, of course, pay a lot of attention to bilateral trade and economic issues, but I bet he will bring up regional and global issues on which the U.S. will seek China’s cooperation. So that is not something that, if you ignore it, it won’t exist. It always exists there. You cannot simply ignore or neglect it.

Last but not least is confrontation with China over Taiwan or other issues. The risk is too high; the price is unaffordable to the U.S. There are still people in Washington who believe that it is worthwhile to fight China over Taiwan as part of its grand strategy. I think some people in the U.S. are coming to realize that is a nightmare for the U.S. The U.S. has no chance to win a conflict with China over Taiwan: the price will be too high; the cost will be unaffordable. If we look at U.S. allies in this region, I guess not a single U.S. ally or partner would support the U.S. if it were going to get involved in a conflict with China over the Taiwan issue. So, I think this is a bottom line that the two leaders, when they meet, should not only talk about trade and economic issues, but most importantly the Taiwan issue. I had expected Dan to share with us some of his thoughts about how to successfully manage the Taiwan issue under very challenging circumstances of bilateral relations, but I guess in Washington maybe a rational voice is simply politically incorrect. But this is the very issue I really worry about. Thinking about all the problems in bilateral relations, I think this is the only issue that will bring our two countries to a head-on conflict, and which will have broader ramifications for the region and for the world. So, every time we talk about China–U.S. relations, we should always remember Taiwan is the single most important issue in this relationship.

With that, I will stop here. Thank you.

QUESTION & ANSWERS

Moderator (Professor Wu Xinbo):

Great speech and great comment as always. So now we will start the Q&A session.

Audience Member 1 (Charlotte, NYU Shanghai / Duke):

My name is Charlotte. I’m visiting from the U.S. this semester studying at NYU Shanghai but originally at Duke in the U.S. My question is about people-to-people diplomacy. As Ambassador Kritenbrink noted repeatedly, diplomatic and people-to-people engagements are of utmost importance but have limits and ceilings on the effectiveness of this form of diplomacy. So, how do we institutionalize these mechanisms and these working groups so that they can withstand both the political swings of both domestic systems, but also swings in the stability of the relationship itself? And is this even a possible task? Thank you.

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

Thank you very much. You said your name was Charlotte? Thank you very much. I think you probably heard through my comments that I’m a true believer in people-to-people diplomacy, people-to-people ties, in part because I benefited from the power of exchange and educational exchange. When I was a young person—maybe around your age—growing up in the great state of Nebraska, and somehow on a small farm in a very agricultural, sparsely populated state, I discovered the broader world because professors who believed in me decided to give me an opportunity to study abroad in Japan. That was one of the early life-changing experiences for me that taught me the importance of really understanding other peoples, other countries, cultures, and languages.

I mentioned my experience here as a diplomat in my first assignment. I was working for the great Susan Thornton, one of the best American diplomats I’ve ever known, a great boss and a former Barnett-Oksengerg speaker. I was very early in my tenure, and she came to me and said, “I didn’t hire you to manage your inbox. So, get off your backside, go out and start meeting with people, and understand something about this country, and then write something to Washington to teach them as well.” Those are just a couple of examples. If we don’t have those experiences, then I will be incredibly pessimistic about the future of our relationship.

I don’t have any magic solution for how to institutionalize it. But what I do think is that we collectively have to stand up and say that these exchanges are important. No matter what’s happening between our governments, our people have to understand one another. They have to respect one another. I mentioned that I studied under the late, great David Newsom at the University of Virginia. He was one of America’s finest diplomats. He talked about diplomacy as being based on relationships of trust and mutual respect. I think people-to-people diplomacy is also based on trust and mutual respect. Only when we meet as human beings together can we discover what we have in common. Only if we trust one another and respect one another can we have really blunt conversations like the one that Dr. Wu and I are having here today.

Sometimes we can’t wait for our leaders or our governments to figure that out. Even as we try to encourage them not to take steps to limit those exchanges, I hope that our peoples will continue to engage in those activities no matter what. So I commend you for coming here. I’m sure it’s been a great experience—I certainly hope it has. We need more of that, not less. Thank you.

Professor Shao:

Yes, I agree. We should start by ourselves. So although I was interrogated when I visited the United States this past June, I am planning my next visit to the States now. So let’s do it together.

Jan Berris:

Can I just add one thing? That’s something that at the Committee we think about constantly. Charlotte, I would say that you and your friends who are here studying—you have a role to play in that. When you go back home, you need to tell your teachers, the administrators at your university, your neighbors, your friends at your church or your synagogue or wherever you find people who will listen to you about your experience and how those affected you, and how they have changed your life, perhaps as Dan’s experience in Japan changed his. Our leaders have to hear from those of us who have actual on-the-ground experiences.

The media—neither American media is in China nor Chinese media in America—and so people, in these days of fake news, make things up. Our leaders now have very contentious views of one another. So it has to be the people themselves who’ve had these experiences. It’s incumbent on you. We want to charge you with going back home and talking to people about what you learned and how important it is for others to come here and learn, and vice versa.

And apologies to you on behalf of the American people for what you had to experience at the airport. I would say that both of our governments are guilty of not trusting the exchange relationship and causing too much “ma fan” (trouble) at our borders when we’re letting the other side’s people in. So Charlotte, “jia you”! (Keep moving forward!)

Moderator (Professor Shao):

Thank you, Jan. So we have to “bu pa mafan” (not fear trouble). Next question or comment?

Audience Member 2 (Professor Qin, Fudan University):

My name is Xiang Qin, from the Center for American Studies at Fudan University, and Professor Wu is my boss. I want to raise a question because I agree with what Professor Wu has talked about on the Taiwan issue—of course, not only because he’s my boss. I think most of the people in this room know Taiwan issue is the most dangerous structural problem between the two sides. We noticed that last month AIT issued a kind of statement that seemed to challenge the Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Proclamation, and also challenge UN Resolution 2758. I think it’s a kind of new movement made by the U.S. government. Could you tell me your interpretation of such behavior and what’s the intention or implication of that? Thank you very much.

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

Thank you, Professor. I assume that’s directed at me. Let me say two things—well, I’ll probably say more than that. First, I’m no longer a U.S. diplomat. I retired in January this year. I’m now a Partner at The Asia Group, where we try to help companies succeed in Asia and help Asian companies succeed in the United States. But I’ll try to speak candidly based on my past experience and my understanding of what I think is going on. I haven’t been in the government since January, so I don’t know exactly why that statement was made at that time.

Here’s what I would say about the issue of Taiwan and cross-Strait relations. I think the great wisdom of our forefathers at the time of normalization was to advance common understanding between the United States and China as much as possible. On the Taiwan issue, we could only get so far. I think we did share certain understandings and based on those understandings we were able—under President Nixon and Secretary Kissinger—to open a path toward normalization, and under President Carter we were able to normalize.

But the reality is, because there were certain fundamental differences that remained between the U.S. and China over the question of Taiwan, very clever diplomats on both sides came up with sufficiently clear yet vague language that we both respectively call our “One China” policies. You call it the One China Principle; we call it the U.S. One China Policy. The reality is that language and that formulation masks the fact that our countries don’t fully agree with the situation. But what we did agree, essentially—being informal here—is that we agreed to put that issue on the shelf, and that over time that issue would be resolved. That would be my shorthand, informal summary of the issue.

I remember when I first started working on the U.S.–China relationship, in recognition of how sensitive that issue was, I was given a laminated card with America’s One China Policy on it. And I was told that if I ever said a word about Taiwan that was not on that card, I would get fired. That’s a recognition that our One China Policy is rather complex, somewhat sensitive—but I think it proves the point.

I think what your American friends think, and what I thought when I was in the government, is that Chinese friends are increasingly dissatisfied with that status quo and increasingly dissatisfied with the ambiguity around those issues. So, most of your American friends, particularly those in government, believe that China is trying to push and alter that status quo through its series of measures. So when I saw the statement by AIT on UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 and on the Cairo and Potsdam declarations, I wasn’t involved in that decision—I’m now a private American citizen working for a private company—but the way I interpreted it was: in recent years, Chinese friends have become much more aggressive about pushing their interpretation of UN Resolution 2758 and of Cairo and Potsdam. I think you would probably argue your position has not changed over the years on that, and I would agree with that. But I do think Chinese friends have been more aggressive about pushing that issue to try to make progress from Beijing’s perspective on Taiwan.

I think your American friends are pushing back by saying, “Here’s our interpretation of those events, it’s different from yours, so don’t use that language to try to upend the status quo.” That’s what I think is going on.

This issue is very complex. It’s incredibly emotional, particularly for friends on the mainland. I think it’s emotional for friends in Taiwan and for many of your American friends as well. I still think we are better off when we stick to the wisdom of our forefathers and continue to embrace the status quo and the ambiguity of our One China policies. I think that is the recipe for peace and stability going forward.

That’s the American perspective that I think I can share with some confidence, but I’m not speaking on behalf of the U.S. government. That’s my view of what I think is going on. I don’t necessarily expect you to be convinced, but I hope you’ll understand that that’s what many American friends think. I think many American friends are worried that China, over time, may be willing to use non-peaceful means to solve the cross-Strait issue. I think your American friends believe let’s preserve the status quo on peace and stability, and this is an issue that will be resolved in the future.

Professor Wu Xinbo:

I have to jump in. Dan just mentioned that in the past as diplomats they had to be very cautious in talking about the Taiwan issue. This kind of sensitivity shaped the U.S. approach to this issue for a long time after normalization, and Taiwan was not a major issue in bilateral relations for many years, until very recently—not because the mainland tried to pursue some new agenda; that has been our consistent policy all these years.

What’s changing, in my understanding, is that in Washington people began to rethink the Taiwan issue in the broader context of strategic competition with China. To put it another way, some people are rediscovering Taiwan’s strategic value to the United Statesin its competition with China, and they began to move back on their Taiwan policy, including challenging historical documents regarding Taiwan as one part of China. I think that’s something making the Chinese side not only very upset, but very vigilant.

I think one thing U.S. friends should bear in mind: as long as we still care about U.S. positions on the Taiwan issue, that’s a good sign—that we still take the U.S. factor into account when we think about Taiwan. However, if one day we just ignore the U.S. factor, we don’t care what U.S. Taiwan policy is, that may not be a good thing for the U.S. on the Taiwan issue.

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

Thank you. I normally pledge, if I want to have a productive conversation with Chinese friends, not to talk about Taiwan, and you can tell because it’s still very sensitive. I would just say this: I do know, from the American position, peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait is vitally important. I think for the region, for the world, and for U.S.–China relations. I think we should focus on the status quo. We should probably talk less about 2758 and Cairo and Potsdam. If we do that, we’ll probably be better off.

For the young students in the audience: if you care about U.S.–China relations, you should probably study the history of the Taiwan issue, because it will remain vitally important going forward.

Dr. Shao Yuqun:

I agree with Dan’s point that the Taiwan question is very emotional for all of the Chinese people. But I would say that the Chinese leadership has made and implemented our policy with great strategic patience. Taipei, Beijing and Washington have different understandings of the so-called status quo. Right now, the DPP authorities’ policy towards mainland China has been very provocative. So the Chinese mainland’s policy has been to deter the DPP authorities’ policy and to try to stop the United States from sending wrong messages to Taiwan.

I agree the young people should learn the history of the Taiwan question, and also I think it’s very important for Washington now to have real experts on China and on the history of the Taiwan question, in order to avoid the kind of mistake that Secretary Bessant made about our Vice Minister,

Moderator (Dr. Shao):

Okay, next question or comment.

Audience Member 3 (David, Fudan alumnus):

Thank you. I’m David. I’m an alumnus from Fudan University. I have a question for both the Ambassador and Professor Wu. If you swapped your positions—advisory roles—I mean, if Ambassador, you advise the leadership of China’s central government, like our President, and Professor Wu, you advise President Trump, and purely based on the interests of the country: what is the one difference that you would advise the government to do very differently from now, based on their interests? So Ambassador, based on China’s interests, what would you advise our President to do very differently on foreign policy, and Professor Wu, based on U.S. interests, one thing you would advise the U.S. government to do very differently?

Ambassador Kritenbrink:

Can I just say, that’s the best question I’ve ever heard—that is really good.

Professor Wu Xinbo:

My job is easy. If I’m going to advise Donald Trump, I will say, “Mr. President, if you are serious about making America great again, let’s fix relations with China—switching from competition to cooperation. Because today, only through cooperation with China can we improve our infrastructure, reinvigorate our manufacturing capacity, stabilize our financial system, and deal with the drug issue that has plagued many people and households. Only by doing that can we save China’s cooperation in dealing with regional and global issues including climate change, that you may not like but that is really happening. So my job is easy: changing the key word shaping U.S. policy to China from “competition” to “cooperation.”

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

I think your question is a brilliant one. I’ll just give you a reaction on the spot. If I were really in that situation, maybe I wouldn’t give this advice, but this is what I really think. I would advise Chinese leaders maybe not to push as hard. Let me explain: maybe not promote “wolf warrior” diplomacy, and maybe think about the way that China is perceived overseas, and consider that sometimes a softer and friendlier approach may be more successful in the long run.

I mentioned that it was profoundly impactful for me in my first few years in China that I had the opportunity to meet regularly with Chinese friends—to get paid to eat and drink with smart Chinese friends. I learned, as I heard from Dr. Wu today as well, that many Chinese friends think that the United States and the Western world wants to keep China down, that we can’t stand to see China succeed, that somehow we want to continue this sense of grievance from the “century of humiliation.” In all sincerity, I don’t think that’s what the United States is about at all. I think most Americans believe that we as a country, as a society—our companies, our universities, our government—have invested heavily in China’s success and China’s rise.

So I would probably advise Chinese leaders and diplomats to think about that: if you take your diplomat hat off and put on the cap of an academic and be objective about it, I think history will teach us anytime a country rises very rapidly and has new influence, that automatically creates a reaction. I think that’s what’s happening today. We may have different perspectives on that, and you can debate whether you like that or not, or whether you agree with that or not, but that does happen.

So I would encourage Chinese diplomats to think more about that. When friends abroad raise concerns about something that China has done, or the impact of Chinese economic or foreign policies, that doesn’t mean that that person or that country wants to keep China down. It probably means that person or that country has a legitimate concern that it wants to raise. The best conversations I have ever seen between our leaders and our diplomats were conversations like that—where there were no cameras, complete privacy, and complete honesty, trying to take out emotion and be objective. That would be my appeal. It’s probably hopelessly naive and idealistic, but that would be my advice. Thank you.

Audience Member 4 (PhD candidate, Fudan University):

Thank you Professor Wu and Ambassador Kritenbrink. I’m a PhD candidate at Fudan University. I have a question for the Ambassador about strategic competition. Trump initiated the trade war in 2018, and then the Biden administration launched technological sanctions—for example on 5G, AI, and semiconductors. Since the U.S. government created such strategic competition, how and why would you think that they should manage the problems that were created by themselves? I want to hear your perspectives. Thank you.

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

This is why I think dialogue is so important. I think for many of your American friends, they would say the U.S. didn’t start this competition. Again, I’m not trying to play a blame game here. I have had many great conversations with Chinese friends over the years, and I would say: “My friends, I read your leaders’ speeches, I try to read the Renmin Ribao (at least I used to), I try to read the Huanqiu Shibao (Global Times), even though it makes my blood pressure rise. In reading those policies and statements, it’s very clear to your American friends that China has had a competitive approach to the United States from the beginning—that China viewed the U.S. in very complex ways, some positive, some negative, but certainly in very competitive ways. And I think the competition with the U.S. really spurred China to action.”

So I think probably the majority view on the U.S. side would be that the United States—both the government, the business community, academia—were responding to, in our view, competitive actions from China that we thought were unfair, and therefore we were taking steps to wake up to that reality and deal with it.

Dr. Wu a little while ago said that he saw America’s embrace of this competitive relationship as showing that Americans can’t stand to see China succeed. I don’t know a single American who thinks like that. I do know a lot of Americans who believe that now that China has risen to a place where it has certain stature and influence, China is using that influence. American friends would believe that while China deserves credit for its rise and success, some of that was done unfairly—if you ask some American companies who have invested here or whose intellectual property rights have been acquired or stolen over the years.

So when you ask me how can America fix the mistakes it’s made and fix the strategic competition that it started, I wouldn’t say, “No, you started first.” I would say that. I would just say: the other side always has a perspective. I hear your perspective and I respect it. I fundamentally believe that you sincerely believe it. I just want you to understand that many American friends in and out of government, who believe that China has taken steps that were harmful and unfair to the United States. We’d love to see China succeed; we just don’t want it to be to our detriment.

We can debate who’s right and who’s wrong, but the reality is both sides fundamentally believe that, and that’s the challenge that I think we have to manage. That’s why I mentioned a little while ago that I think dialogue like this is so important; it’s why I feel diplomacy is so important.

I don’t disagree with everything that Dr. Wu said, but I do disagree with a couple of things. Whether you like the style of diplomacy underway right now between the United States and China or not, there still is diplomacy. Our leaders are going to meet, and I’m glad they are going to meet. I would say the relationship between our two presidents and the diplomacy between them is probably the best thing going in U.S.-China relations right now, and is the single greatest contributor of stability to the U.S-China relationship. That’s very untraditional. And the fact that both sides want something out of that diplomacy and are working very hard to get it is a good thing.

I was asked by Bloomberg today, who got the better end of the deal in Kuala Lumpur? Who won and who lost? I politely said, I don’t agree with the question: neither side would have agreed to this meeting if we didn’t think it was in our interest. So it’s pretty clear to me that both sides are getting what they wanted. Not everything they wanted, that’s diplomacy.

My professor Ken Thompson once said to me “if you want to want to understand international relations, go talk to my wife.” And I sort of feel that way as well. Neither side gets exactly what they want. That’s life, that’s diplomacy. I think it’s a great thing our leaders are meeting; I hope it’s a successful meeting; I hope we have a schedule of meetings between our presidents in the year ahead because I think that gives us the best option for stability and certainty and cooperation.

Professor Wu Xinbo:

Well when Dan says he doesn’t believe America wants to hold China down, I think sometimes diplomats have to speak diplomatically. Check with people like Matt Pottinger or some of his colleagues, but maybe they are exceptions.

When teaching international relations at universities, I always tell my students that competition is a norm in international relations; countries are inclined to compete with one another. That’s very normal. But there’s a difference between types of competition. When China says, “I want to learn from the U.S., I want to catch up with the U.S., I want to narrow the gap with the U.S. by improving myself and increasing my capability,” that’s what we call benign competition, constructive competition. You keep improving yourself.

Another way of competing is trying to keep the other side down, trying to damage the other side. If you look at what happened after Donald Trump, during his first term coming up with the notion of strategic competition with China, it was followed by unprecedented tariffs on China, by ever tighter technology controls over China, by ever increasing sanctions against Chinese entities, by more and more nuclear pressure on China. That is not what we call benign or constructive competition. That doesn’t actually help enhance U.S. competitiveness, as I mentioned in my comments. So yes, competition is normal, but there are differences between different kinds of competition. What’s upsetting to the Chinese side is that some people in the U.S. believe the only way for the U.S. to win is not so much to improve itself, but to keep China down. I think that’s the problem.

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

One final comment: we Americans like to think we’re capitalists; we love competition, we just want it to be fair. But to go to the young lady’s question, many friends in the United States think that competition over the last couple of decades has been unfair, and that’s why you’re seeing the response from the United States. Now some Chinese friends will say, “See, that shows the Americans can’t stand to see China succeed.” Sorry, but I still know very few people who think that way. I do know a lot of Americans who think China’s form of competition has been unfair.

So now we both think the other side has been unfair. Alright? So what are we going to do about it? It’s going to be your responsibility and ours to have this kind of exchange to try to understand one another better. If we understand one another better, then we have a chance.

I mentioned a moment ago, it made me kind of sad to say this: I’ve delivered a lot of demarches – hundreds of thousands of them, probably. I don’t think that’s going to solve the issue. But dialogue is part of it, and then our two countries have to do the best we can. But I do agree; we don’t want have zero-sum competition. I think we can both succeed. That’s my hope.

Audience Member 5 (Gabriel, Johns Hopkins Nanjing Center):

My name is Gabriel and I’m part of the student delegation from the Nanjing Hopkins Center. Thank you for this opportunity and thank you for reminding us about the importance of trust and people-to-people connections. Many commentators say a big issue in U.S.–China relations is a mismatch in expectations between the two sides. Events like this one today help both sides understand each other, but what do you think remains of that challenge, and managing expectations, and what can leaders in South Korea or in the future do to overcome it?

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

It’s a very thoughtful point. I would also say that the issues we’re discussing here are maybe more serious and more pointed because the stakes are so high between the United States and China. But when we talk about trust and mutual respect, that’s the foundation of every bilateral relationship in the world; it’s the foundation of every personal relationship in the world. I think you have to start there.

Having a modicum of trust and being respectful doesn’t mean you have to pull your punches or be dishonest. I think Dr. Wu and I have been pretty honest here today—I think Dr. Wu has been maybe a little more honest than I have, but that’s okay, this is his home turf.

In all seriousness, the importance is what we do about it. I would say this, too. I tried to be careful in my remarks. One of the reasons why I hesitated when Jan gave me this great honor of asking me to do this. These issues are so difficult and emotional, I felt like I was going out on a high wire and I didn’t want to fall off. But having come here and had this really rich discussion and getting all these great questions, I’m really glad we’ve done it.

I think we have to make one another uncomfortable. We have to speak the truth to power. If we do it in a context where we’re being respectful, I think that’s fine. I’ll go back to the point about diplomacy. Someone asked me the other day if it’s really worthwhile to have diplomacy with the Chinese. There are some friends in the U.S. say that’s a waste of time. You can tell I fundamentally disagree with that. I have great respect for my Chinese diplomatic counterparts. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t have spent so much of my adult life talking with them and trying to work with them to manage this relationship, to at a minimum prevent miscalculation and conflict, and maybe through hard work and some kind of mutual understanding, maybe do better and actually get something positive done. I’ve seen that through our presidents as well

We wouldn’t waste our time negotiating with Chinese friends if we didn’t think it was worthwhile and if we didn’t think that the that agreements that we concluded would be adhered to. If you asked diplomats on both sides, they would probably say the record is not perfect on either side, but both sides still believe in doing it because of what I’ve said: there is still a modicum of respect and we have to preserve that. If we do that, I still think we have a chance.

Audience Member 6 (Luca, exchange student at Fudan):

I’m Luca Beril. I study on an exchange at Fudan. I wanted to ask about the Russia–Ukraine war and whether you think this is going to be on the agenda in the meeting coming up, and if so, what would be the priorities for that, especially given the last attitude of President Trump towards Ukraine?

Ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink:

That’s a great question. I do think it will be raised. I don’t know exactly how it will be discussed. I want to be very candid with Chinese friends: I have been deeply saddened and shocked by China’s support of Russia in Ukraine—Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine. This is another difficult, emotional issue, and one I’ve debated multiple times with Chinese diplomats. I don’t want to debate the issue, I just want to share with you many of your American and Chinese friends have been confused, and saddened, and angered to see China’s support for Russia and Ukraine.

The reasons are multiple. One reason for me is that I thought the 70-year tradition since China’s founding was to hold respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of nations as something central to international relations. This was the most precious and sacred principle. I feel like China has strayed from that in this instance, in the name of advancing other interests. The second reason: it was striking to me during my last job, during which the Russian invasion of Ukraine occurred, how much European and Asian friends were united in supporting Ukraine. Why? Because friends in both Europe and Asia recognize that if any country in the world can redraw borders at whim, I think the world becomes a very dangerous place.

So I do think the issue will be raised. I don’t know how. You mentioned accurately that President Trump’s own views on this issue are quite complex, but I do just want to state how profoundly disconcerting China’s policies on Ukraine have been. You’ll recall that one of China’s neighbors in the region said, “Ukraine today, Asia tomorrow.” That’s the concern.