National Committee Vice President Jan Berris, who joined the organization in 1971 specifically to work on the visit of the Chinese Ping Pong Team to the United States, participated in two events in China this April, one in Shanghai and the other in Beijing, that celebrated the 50th Anniversary of Ping Pong Diplomacy. A 15-minute excerpt of her hour-long Shanghai interview and the transcript can be found below.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

Q: Where were you when the American table tennis delegation visited China in 1971?

JB: I was in Hong Kong in April of 1971 when the Chinese table tennis team surprised the entire world by suddenly inviting the American team to stop off in China on its way home to the United States.

I remember very vividly that I was on my way to dinner with some friends and I saw this newspaper headline. I thought this can’t be true. I was very suspicious because in those days many of the Hong Kong papers were not devoted necessarily to the news, but to sensational stories. So I just thought this was one more sensational story.

I told my friends at dinner what I’d heard, and they said they had heard rumors of that as well; and it may in fact be true. We spent most of the dinner talking about that and what it might mean and what an exciting change it would make.

Q: Did you know at the time that the visit of ping pong team would also change the course of your own life?

JB: No. I thought this was a historically interesting thing, as an event on its own, but I didn’t realize the life changing impact it would have on me.

I was leaving Hong Kong in late May, early June of 71 because I had finished my two-year tour of duty as the assistant cultural affairs officer at the US Consulate General in Hong Kong. I returned home to Michigan, where my family lived for a month-long rest. When I was about two days away from leaving to go to Washington to train for my next position, which was going to be in Indonesia, I received a telephone call from two former professors, who asked me if I would consider taking a year’s leave of absence from the Foreign Service, and go to New York and work for the National Committee on US-China Relations. Both of them were on the Committee’s board, and since it was going to be co-hosting, along with the US Table Tennis Association, the visit of the Chinese ping pong team sometime in 1972, they wanted someone on the staff who had had some diplomatic experience. But I wasn’t really sure if I wanted to do that.

That happened to be around the first week of July of 1971. People who know the history of US-China relations will remember that it was on July 15, 1971, that President Nixon announced that Dr Kissinger had made a secret trip to Beijing. So that made my interest in going to New York much stronger. It was a potentially really exciting time and there was the possibility that things between the two countries might develop very quickly. In fact, all of my colleagues in Washington in the Foreign Service, said I would be crazy not to go to New York and to the National Committee. So that’s what I did – thinking that it would be for a year; yet 50 years later I am still here!

I should say that while Ping Pong Diplomacy was a major and really important development that marked the beginning of a whole new era in the history of the relationship between China and the US, it also marked a major turning point in my own life.

During the Chinese Ping Pong Team’s visit to New York in 1972, Jan Berris (second left) and her parents meet Chinese Ambassador Huang Hua and table tennis captain Zhuang Zedong.

Q: In 1972 the visiting Chinese team started off in your hometown Detroit. Why was that?

JB: It was actually a coincidence. There were two host organizations for this visit, the National Committee on US-China Relations and the US Table Tennis Association. The chairman of the National Committee at that time was Alex Eckstein, an economist at the University of Michigan and one of the professors who had called me. The University is in Ann Arbor, about 40 minutes’ drive from Detroit. The chairman of the US Table Tennis Association that year was Graham Steenhoven, an automotive worker at the Chrysler Motor Company based in Detroit. So the chairmen of the two co-host organizations happened to be living within a 30 mile distance from one another. That’s why the first stop was in Detroit.

The first exhibit game in Detroit took place in a large arena, where professional basketball players and hockey teams used to play. When the Chinese national anthem began to play, there were some very right-wing extremists who began making noise and not acting appropriately at all. So the security hustled them out very quickly, and the event went on, and was very successful.

Q: You toured with the Chinese ping pong team throughout their visit in 1972. What was it about that experience that left you with the most indelible impression?

JB: I suppose the thing that stands out the most and what always struck me, both at the time, although not quite when I was living it, but shortly thereafter, was how easy it was to move from a period when people in two countries who had been conditioned by their governments and their media, to think of the other as enemies, how quickly they were able to overcome that, and change the negative stereotypes that our two peoples had had of one another.

While we were not involved in the 1971 visit of the American team to China, just in the reciprocal visit to the United States, we were involved from then on in all of the exchanges that took place up until 1979 when we normalized relations. Mostly starting out with athletics and performing arts, but gradually adding in other professional exchanges. The next one we did was the visit of the Shenyang zajituan (acrobatic troupe).

NCUSCR’s board delegation meet with Chinese premier Zhou Enlai (sixth left in the front row) in 1973. Jan Berris is first right in the second row.

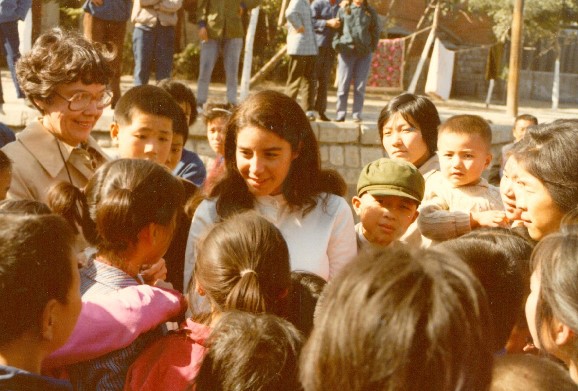

Jan Berris and a Chinese co-announcer during the Chinese Martial Arts Team’s visit in the US in 1974

We also hosted every athletic team that you could think of. We had soccer, basketball, volleyball, swimming, diving, tennis, and track and field teams – among others. Through all those exchanges, we either hosted the first visits of those kinds of athletic teams to the United States, or sent the first of an American team in that sport to China.

During that period, the main theme was friendship. It was pervasive. If I had to come up with one phrase that would describe that period, it would be 友谊第一,比赛第二 (friendship first, competition second). The Chinese started off saying that all the time. Gradually even our security detail, who spoke no Chinese whatsoever, or the American ping pong players, everybody learned that phrase: 友谊第一,比赛第二.

I remember that spirit of friendship was apparent not just on the ping pong floor or in later years on the soccer filed or the basketball court, but it was also true of the relationship between the people.

Q: How did the American people respond to the visit of the Chinese delegation?

JB: It was a very high profile exchange. We wanted people to know about it. We purposefully made the ticket price inexpensive so that more Americans could come and see the events.

Lots of people, whether journalists, the American players, or ordinary Americans the delegation would meet, would usually ask one of the Chinese: What has impressed you most about your trip to the United States? Invariably, whether it was asked of one of the ping pong players, or a team official, or a Chinese journalist accompanying the delegation, the answer would be some variation of what impressed us most is the warmth, friendship, and kindness that’s been shown to us by the American people.

The first few times I heard that response, I thought to myself, they really don’t think that, it’s something they were told to say, as it sounds good and it’s very diplomatic. But as I traveled around the United States with the team, I found that that was the answer that I would have given too, because I was enormously impressed by how open the American people were, and how generous, how warm and how hospitable they were.

Q: Did the American people also change their views of the Chinese people, after meeting them in person?

JB: We had been taught that people from Communist China all dressed alike, said the same things, and acted alike. But of course, the Chinese delegation members all had their own personalities, their own likes and dislikes, etc. This was certainly true of the people on the ping pong team, but also true of subsequent delegations that we hosted. I think they must have been handpicked not just for their great athletic ability or other talents, but also because they were very warm, outgoing people with good personalities. They were extremely talented, and they had the ability of charming everybody that they met – including me!

After I came back from each delegation that I traveled with, I would call my mother to tell her about the trip and she used to tease me by saying: well, tell me about all the new best friends you’ve made from this delegation.

Q: Were there any interesting anecdotes or incidents during that 1972 visit?

JB: Despite all of the warmth and friendship, there were problems. There were people in this country who were very upset that we were hosting people from a Communist country. Some of those people made their feelings known by demonstrating.

What sticks most in my mind is an event that happened when we were performing on a basketball court at the University of Maryland. Tricia Nixon, the oldest daughter of President Nixon, was attending the event representing her father. She was sitting in the audience along one of the long ends of the court; and on the opposite side were about 200 supporters of Taiwan. Up in the balcony on one of the short ends of the court, were lots of anti-war activist students who were very angry at President Nixon because the day before he had ordered the re-bombing of the harbor in Hai Phong – as we were then in the middle of the Vietnam War.

The Taiwanese were very loudly yelling for all the Chinese players to defect from China. The American students were stomping on the wooden bleachers and shouting: “Tricia watches ping pong, Nixon bombs Hai Phong” over and over again. Meanwhile, Tricia Nixon sat very quietly through this huge uproar. I was sitting at a small table on the floor with the announcer, as one of my several different jobs during the trip was to help announcers pronounce the Chinese players’ names correctly. I was frantically telling him: just say something, talk, you’ve got to do something to overcome all this noise!

So that is one of the most vivid memories that I have of the whole ping pong trip.

Q: Did the events attract a lot of media attention at the time?

JB: This was the first time any Chinese national had set foot in the United States since the founding of the PRC. So it was a very big story not just for the American media, but for foreign media as well. Thus, we had huge media coverage. All the major newspapers, television channels, wire services, and magazines were represented. The Chinese side also brought a large media contingent, including Xinhua, People’s Daily, and two documentary teams. In fact there was so much attention that we had to hire two people just to take care of the journalists. And when we were traveling to other cities, we even had two planes: one for the American and the Chinese team members and the accompanying staff members, and another just for the journalists.

Q: Was it hard to bid farewell to the Chinese delegation?

JB: In fact, the other day, to prepare for this interview, I took a look at the half-hour documentary that the Chinese documentary team made on the visit. The final scenes are all of us standing there waving goodbye to the Chinese who were by that point on the plane. We were very sad because we had been with the group for four weeks, and had gotten to know everyone well. I got very emotional and along with some others was crying.

During my first trip to China, which was in June of 1973, about a year after the ping pong visit, I would meet people and they would look at me and say: Oh, I know you. You are that crying girl. So that was me. My nickname was “that crying girl”.

The National Committee on US-China Relations’ board delegation on the streets of Beijing in 1973

Q: It’s been 50 years since you started working at the National Committee on US-China Relations. What has kept you doing this job all over the years?

JB: For my entire career, it’s really the people-to-people aspects of my job that have been the most important to me, and interests me the most. While the work I’m doing sometimes can be the same, and sometimes can be tedious, it is the people that I’ve been able to meet throughout this wonderful job that interests me the most.

While I am in awe of China’s long and rich culture and history, its amazing and beautiful art, its fabulous food and its fascinating political issues, what I really and truly care about are the people, and the relationships I’ve been able to make over the years with Chinese, as you like to say, from all walks of life.

And it is not just the connections that I’ve been able to make on my own, but the fact that the job I’ve had at the National Committee on US-China Relations, has enabled me to introduce thousands of Americans to China, and thousands of Chinese to the United States, and hopefully to help them understand one another a little better.

Q: Some people are now having doubts about the engagement strategy. What’s your view on that?

JB: It won’t be any surprise to you that I believe firmly in engagement. I think it is absolutely essential that people, whether they agree with one another or not, continue to engage with each other, and sit down and talk with one another.

The argument that has recently been put forth by some that the past 40 or 50 years of engagement has been wasted and only benefited China is absurd. I was there in the 70s. The people who were involved in crafting our engagement policy were not naïve. They knew China well and they knew what they were doing.

Those who are now detractors of the engagement policy have mis-characterized its objectives. The goal was never to transform China into a liberal democracy. Instead, the objectives were threefold. One was to enhance Americans’ security by deterring the Soviet Union. Another was to deliberately, and I would add very effectively, facilitate China’s rise, both for its citizens but also selfishly in order to make China a stronger partner with the United States against the Soviet Union. And third, I think it was to ensure that China became a more stable and prosperous country, so that eventually it would become enmeshed in a rules-based order. Those were our three reasons for the engagement policy and I would argue that all three were important and effective.

Yet, the detractors of the policy are not giving any of that any credibility. Nor have they paid attention to the organic growth of the relationship. Finally these detractors don’t talk about what the alternatives would be. If we hadn’t had this engagement, things could have been a whole lot worse than now.

Q: What are the merits of the engagement strategy?

JB: I believe that engagement, despite what the detractors say, benefited the American people a lot. It strengthened our deterrence capability; and therefore helped reduce the danger of a nuclear threat and a Soviet attack on the United States and its allies.

While it’s hard to quantify what would have happened if we had not had the relationship, what is clear is that there have been no major conflicts in the East Asian region in the past five decades. That is in great contrast to the years before that, when the United States was involved very heavily in military operations, whether it was World War II, or the Korean War, or the Vietnam war.

However, it has been peaceful for the last five decades. I attribute a lot of that to the relationship and to the engagement between China and the United States. I also think that that avoidance of war or conflict in East Asia is one of the things that has enabled the region to become the fastest growing and most dynamic in the world.

In the United States, some people hold negative views about China because they think China stole their jobs. Yet study after study has shown that those jobs were lost because of automation, not because China was stealing them. Plus they don’t mention the fact that the dynamism of the East Asia region created a lot of other good jobs here in the United States and has enabled Americans to pay less for goods than might otherwise have been the case.

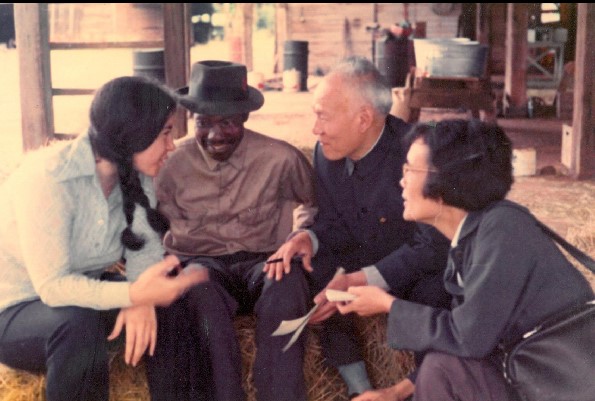

Chinese journalists’ delegation members talk to a Georgia farmer in 1973 with Jan Berris helping to interpret.

Q: What can we learn from the art of diplomacy in the 1970s?

JB: In order to make people-to-people engagement successful, we really have to go back to the early 70s.

In the 70s, both governments actually stepped back, and allowed the people to take the relationship at their own pace. The US government, paved the way by relaxing or removing certain restrictions that we had had that prevented interactions between the two countries. Beijing gradually did the same. This enabled the primary drivers of the relationship to be the private sector.

While the two governments enabled it to happen, it was because of the people – the ping pong players and other athletes, the performing artists, the educators, the business community, and everybody who was involved in the myriad numbers of exchanges that began in the 70s and grew to such great lengths, that we have the enormous web of deep and broad relationships between Chinese and American people that is very hard to rip apart.

The society-to-society dimensions of the relationship grew very quickly. In fact, in some ways it became more significant than the government-to-government relationship that initially made this all possible.

I believe that the decision to allow extensive engagement by individuals and by private entities, was part of, at least on the American side, a broader strategy to add resilience to this new relationship. And to forge a lot of ties, both at the official level and at the unofficial level.

The logic on the American side, was simple but very important: the more people were involved, the broader the scope of the relationship and interests, the larger array of constituencies you would have who would want to keep a stake in the relationship and make it successful.

Q: Do you think that people-to-people ties can still play a role in improving relations nowadays?

JB: I definitely think so. We must continue people-to-people relationships because they are very important. Sometimes I think that our two governments, in fact, don’t necessarily do the right things and I trust more in the people of the two countries to do the right things than the two governments.

Unfortunately on both sides we’ve allowed that relationship to deteriorate. As we all know, we are now all facing great problems. We all have to work that much harder to make sure that we do not let the people in both countries who are opposed to the relationship gain the upper hand.

If the two governments want to engage in tit-for-tat actions, such as tariffs or sanctions, that is their prerogative. Personally I don’t think such actions are useful at all. In fact, much of what the two governments do and say to each other these days is counterproductive. I just want them to let the citizens alone, so that they can carry on whatever people-to-people relations they wish. For the past 50 years, the private citizens of both countries have done a really great job at building this strong web of relations.

The two governments will continue to do whatever they want to one another, or say whatever they want to say, but I believe that both governments need to be careful and make sure they keep those negative actions at that government-to-government level and not encourage citizens to be too nationalistic.

There has always been a lot of talk in the relationship about youyi, or being friends. It’s important to be a pengyou, but it’s more important to be a zhengyou, a friend who is willing to tell their friends on the other side what they really believe, to speak the truth, and to make sure that we are all as open and as honest with each other as we can be. If we are not, then that is going to add to the further decline of that wonderful relationship we had during the high period of engagement.

Q: What are the areas that China and the US can work on together more in the future?

JB: There are many areas that our scientists, our artists, our athletes, etc., have all worked on that have been beneficial to both sides in multiple ways. Student exchanges between the two countries are just one of those areas. I hope to see the continuation of people-to-people relations at all levels.

But there are two areas where there is the most promise of mutual cooperation and benefit in the future. One is the crucially important area of climate and the environment. Our prior government did not necessarily believe in climate change, but the Biden administration does. So does the Chinese government. We must work together on a whole variety of environmental issues for the future safety of the world.

The other area is our public health relationship. We have to work together to share knowledge and information about public health issues, and to, hopefully, prevent the kind of pandemic that the world has just seen. Despite all the contention that is currently taking place, I believe it is imperative that the people in our public health systems find a way to get over the differences that have sprung up in an area where we used to have a great deal of mutually beneficial cooperation. We need to stop acting like children and must find ways to act like mature adults.

When you bring people together who are professionals, who are not told what to say or think by their own governments, they are able to find common ground and common interest in working with their fellow professionals in the same field.

That is why I say that we should get the two governments out of the process and let the professionals and the people come together, learn from one another, and share their knowledge: if we do so, the world will be a much better place.